DEBORAH, France, a day in March:

Sophie and I were sitting outside the lighthouse, smoking. I hadn’t smoked Gauloises in years, but you never forget that taste.

From our bench, the Channel spread before us—slate-gray and restless, dotted with fishing boats that looked like toys against the horizon.

It was hard to find things to talk about. We were here for one reason: to tend to things and prepare for my mother’s death—Sophie’s aunt. But what do you do when you’re not at the hospital except wait?

You could start sorting through things, but only the ones that didn’t feel like an intrusion. It wasn’t right to do that before a person had passed. So mostly, we just talked, cleaned up a little, ate a little. And then we smoked.

We tried to talk about the old days, and Sophie started naming the ships, describing their sizes, what kind of cargo they carried, and how many fish they might have.

That’s what you get for being a lighthouse keeper’s daughter. It was strange that she still knew those things almost by heart, even though she had lived in Paris for fifty years. The fishing business hadn’t changed much in all that time, and neither had her knowledge of it.

After her parents died, she took over the lighthouse. Then, she let my mother move in so she could spend her final years somewhere that meant something to her instead of bouncing between cheap rentals that never quite felt like home.

Ever since Maman’s childhood house was sold off, she had never really settled anywhere, and I think that always gnawed at her.

Sophie, though—she made a life in Paris. A good one. She’d built a career in the academic world, written at least ten, maybe twenty books by now. I can’t remember why we got talking about her books, but somehow it always ends up there with her.

So at one point I just blurted out, “Do you think your books will make a difference?”

She blew out a long ring of smoke in that slow, deliberate way she always had. She had been smoking like that for as long as I had known her. Then she said, “You know, I don’t care if they make a difference. I just care about writing them.”

I blinked at her. “I thought you wrote to change people’s minds. To make them understand why we lost, why May ‘68 never really went anywhere. Are you saying that doesn’t matter?”

She gave a little laugh, almost dismissive. “Of course it matters.”

She sounded like she hadn’t meant to reveal something true. But I knew she had.

I guess I kept the conversation from there—moving it without really addressing what we were avoiding. Sophie had, as usual, become more silent, contemplative.

She didn’t add much to my considerations about this or that except a nod here and there.

We played that game for a while and then I felt queasy and had to excuse myself.

I walked alone down to the beach.

I didn’t want to come back, but of course I had to.

We had things to do … so many things, now that Maman was almost … gone.

But there had been this feeling when I lit that cigarette for the first time in decades … what was it?

After walking almost all the way to Plage de Marais it struck me.

Have you ever felt like something was incredibly important when you were young?

Something that defined you completely , that felt like life itself—and then, as you got older, you just couldn’t see the point anymore?

Maybe you kept doing it, but it became shallow, more of a habit than a passion. Or maybe you stopped altogether.

Whatever the case, time had hollowed it out. What once felt urgent, and essential, just wasn’t the same anymore.

I don’t know how to put it into words. But it’s a feeling that scares me.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that feeling recently.

My first memory of it was a certain New Year’s Day.

It was my first time out in France alone, and it felt so different from going out back home. I mean—what was my home? Salt Lake City. When I went out there, it was to visit Sarah or someone else from our community.

But Sophie—Sophie was different. She was my cousin, yes, but she was from the world, you could say. A strange, unruly world, filled with strange books and strange indifference to rules.

That world unsettled me, but it also drew me in. It was outside. And it felt boundless.

I know it sounds silly, but I remember riding home in the metro with Sophie later that day. We barely spoke, just sat there, looking out the window.

And I was already thinking about how I’d tell my mother we’d had a good time. Of course, my clothes would smell a little, because Sophie smoked constantly. But I wouldn’t tell her that I had smoked.

And you know… I didn’t feel bad about lying. Not then. That guilt came later.

At the time, I just felt exhilarated. It was the most important moment of my life, though I couldn’t explain why. Maybe because it felt like there were so many possibilities ahead of me—so many things I could write about.

And now, fifty years later…

I don’t miss that kind of freedom. I don’t miss being untethered from my family. My mother is dying. My father is gone. The shadows are getting longer. And no, of course, I don’t want to feel trapped like I did when I was young, but—

I want ties. Lasting ones. I want something solid, something that gives me a sense of place. And I suppose I have that now. If I don’t think too hard about my marriage. About what it entails. About what we have to try when I get home.

Hopefully, my husband is better after the latest heart problems. Hopefully, he stays better.

But it’s like—yes. It’s like I never truly found a place where I could both be myself and belong to someone else in a way that felt perfect.

Immutable? Is that the word … ?

And I suppose that’s what I was searching for all this time.

Something that felt right and didn’t just change as the wind blew.

There’s so much more I could say. So much I could reflect on—why I feel this way, why my first marriage broke down, the years in New York, drifting from one person to another, never forming deep relationships.

There’s so much I could say about what went wrong. About what went right.

And about how these fleeting moments in time—lost forever—still matter.

*

I’ve looked at life from both sides now

From win and lose and still somehow

It’s life’s illusions, I recall

I really don’t know life at all

Would you like to share your story – it might inspire one of mine? Read more – I’d love to hear from you!

92-14032025

*

Cover Photo by Eduardo Freitas on Unsplash

Honfleur view – by Rodolphe HÉRAUD on Unsplash

*

Soundtrack: Joni Mitchell – “Both Sides, Now”

*

*

And just as the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little crumbs of paper which until then are without character or form, but, the moment they become wet, stretch themselves and bend, take on colour and distinctive shape, become flowers or houses or people, permanent and recognisable, so in that moment all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and of its surroundings, taking their proper shapes and growing solid, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, all from my cup of tea.

– Marcel Proust

*

SHADE OF the Morning Sun: STORIES – main characters:

Carrie Sawyer Reese – (born: Caroline McDonnell) – recovering addict, searching artist, special-needs-mom in training, and Scottish exile in the U.S. of A.

Jonathan Reese – Carrie’s no-nonsense husband, state trooper and Iraq veteran, fighting to keep his family together and his PTSD in check

Emma Reese – Carrie and Jon’s ten-year-old daughter, dreams of a better future, self-appointed protector of her autistic little brother

Michael Reese – Carrie and Jon’s seven-year-old neurodivergent son, can’t talk much but often calls attention to parts of the world that nobody else notices

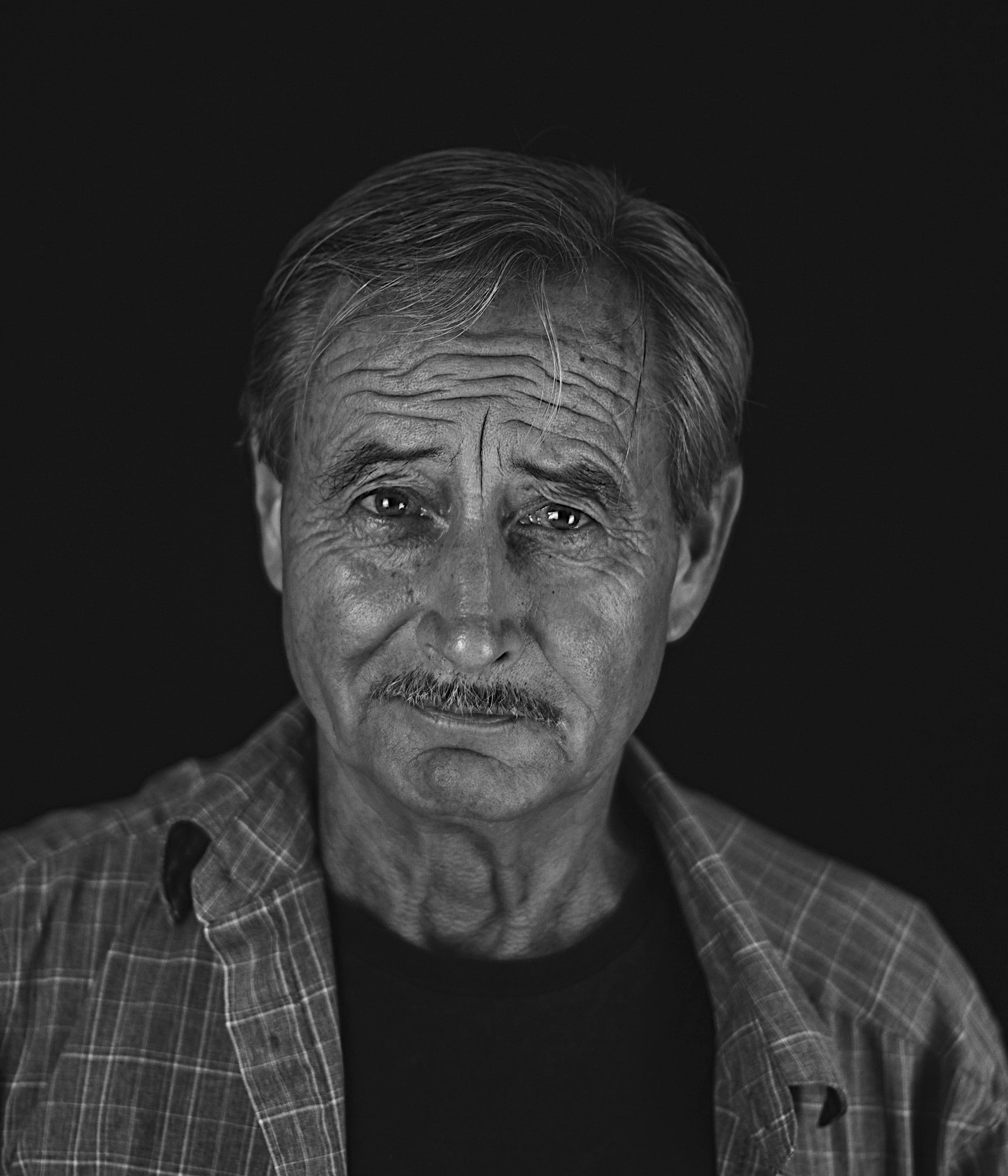

Deborah Sawyer Chen – Carrie’s ex-hippie rebel mother, New Age faith shopaholic and opinionated power-grandma

Marcus Chen Nianzhen – Carrie’s stepfather and Deborah’s second husband. Also millionaire IT businessman and founder of the Church Universal. The man who has everything, except peace of mind …

David Reese – Jon’s little brother, ex-car thief, chronically broken hearted, risking his life in the Sahel with the NGO World Life Health

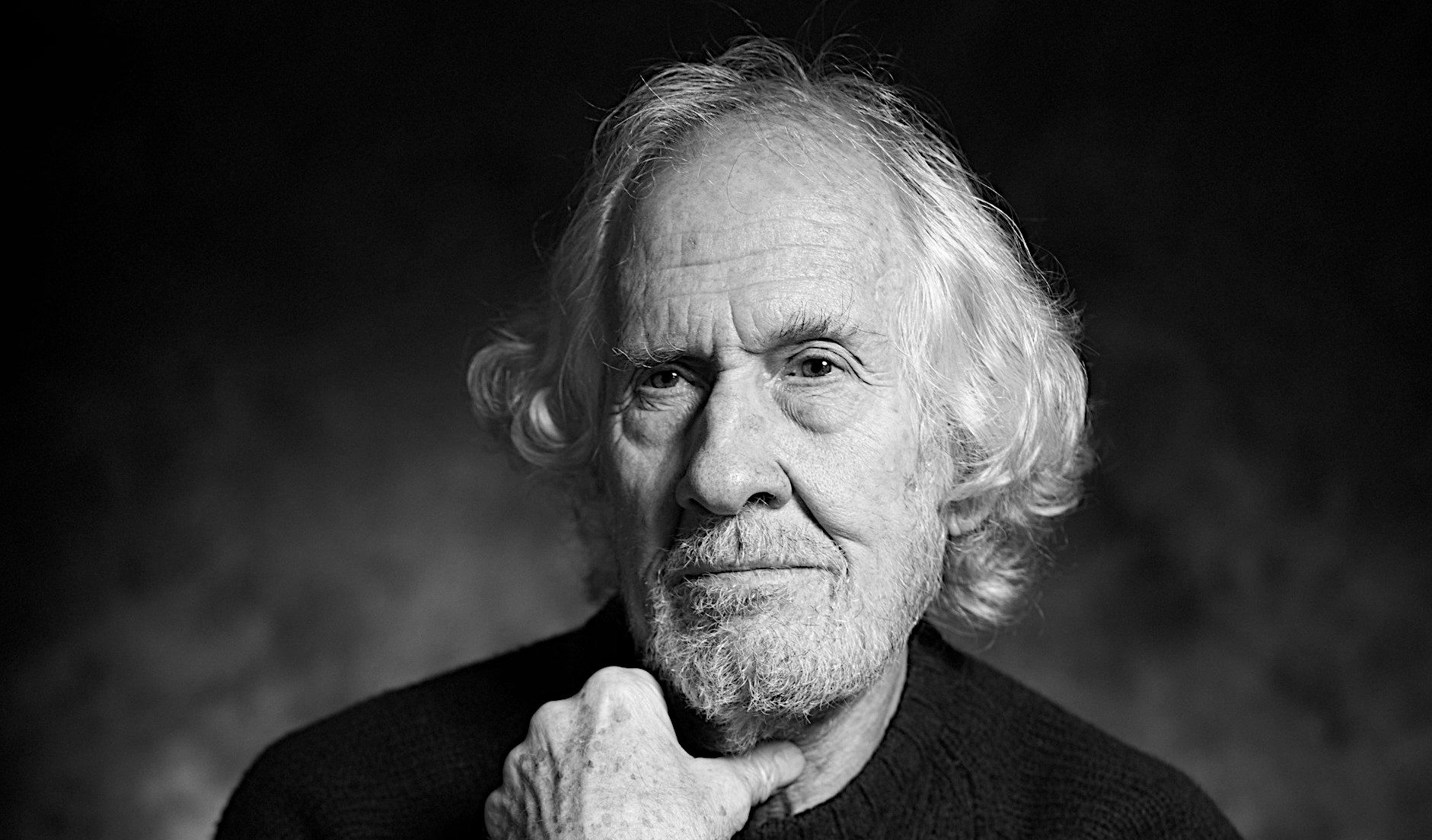

Samuel Reese – Jon and Dave’s erratic father, self-avowed socialist, and fixer of your life

Calum McDonnell – Carrie’s father and Deborah’s first husband, Falklands veteran and ex-Highland Ranger, coming to grips with age and loneliness in far-away Scotland

Thanks to the fantastic photographers at Unsplash and their models. See a collection of all Unsplash photos used on this blog here.

Share a Thought